The Possibility of Transnational Curation and the Search for Belonging in Space: Yael Bartana at the German Pavilion

Diren Demir

22.07.2024

The concept of the 2024 Venice Biennale is “Strangers Everywhere”. As I wander the streets of Venice, immersed in the beautiful fabric of the city, I laugh as I see the intense flow of foreign tourists surrounding the city – including myself – and I read the fiction of this theme spreading from the biennale to the city as a playful intervention. This playful intervention, which spreads across Venice by making the intimate narratives of exile, migration and displacement stories its main focus, seems to disturb many arguments and mindsets that can be considered anti-foreigner even with the superficial experience of being a “tourist” outside the exhibition spaces. Like many other biennials in history, the 60th International Venice Biennale opens amid boycotts, reactions, criticisms and “political unrest”.

One of my initial impressions was how almost every pavilion’s curatorial text prominently featured the term “political unrest” multiple times. In an era where rising polarizations and conflicts escalate into massacres, genocides, war crimes, ecological disasters, and ethnic cleansing, the reduction of such atrocities to mere “unrest” seems to stem from the privileged vantage point of those observing these crises from a distance. This approach, I feel, serves to maintain the status quo rather than challenge it. Writing about the 2024 Venice Biennale inevitably involves facing with the shadows of contemporary political and socio-geographic conflicts—a reality reflected in many pavilions.

While the Biennale provides significant space for Indigenous art, ethnic values, traditional motifs, rituals, and minority artists, there exists a silent discord between the authenticity of Indigenous art and the sterility of conceptual texts. These texts often fail to adequately analyze the current global atmosphere. This dissonance appears rooted in the power imbalance between the privilege of the outsider and the position of the art practitioner, as well as in the Biennale’s structural framework. By dividing the exhibition according to nation-states, it reinforces “state showcases” rather than amplifying the voices of peoples. Even pavilions offering self-critique—such as Australia’s acknowledgment of its colonial history and criminalization of Indigenous and minority artists until recently—operate within this conventional framework, creating tepid and manageable forms of resistance rather than transcending the concept of the nation-state.

While searching for traces of a collective understanding that can go beyond the idea of nation and state, on the second day of the biennial, I find myself at the German Pavilion, in front of Yael Bartana’s installation “Light To The Nations”, which refers precisely to the idea of nation. The theme of the pavilion, curated by Çağla İlk and hosting Yael Bartana and Ersan Mondtag in Giardini e Isola Della Certosa, is “Thresholds”. The exhibition begins by stating that “In a time of uncertainties and catastrophes, borders and thresholds” have a special meaning: “The border as a place of burdened experience and pain, as a camouflaged place of division, is also and always a temporary space. Because the border, with its divisive and obstructive nature, makes us aware of the ephemeral nature of human existence and what potentially awaits us. For it is only through its existence as a line that a threshold can become a place that imagines a common future starting from the here and now. Threshold’s contribution aims to engage with this border, becoming a threshold, and the dreams and stories associated with it…” (1)

Remembering that the thresholds that open new epochs and create revolutions have always emerged in the wake of historical crises, global and regional devastations – or “unrest” as many other pavilions superficially suggest – I feel that a new threshold is approaching for all of us, and that the topic addressed in the German pavilion is very relevant and timely. Çağla İlk’s curation comes from a vision revisiting “places of sorrow” , and it also looks at the future through the experience of these thresholds and historical burdens, opening up space for us to imagine new thresholds, dystopias and utopias. With Yael Bartana’s works, the thresholds mentioned go beyond a socio-political reading of political borderlines or the periodic thresholds of historical crises, and create a space for a spiritual and fictional experience of the future.

Yael Bartana (b. 1970, Kfar Yehezkel, Israel) describes herself as an “observer of the contemporary.” Using art as a scalpel to dissect power structures, her work oscillates between the sociological and the imaginative, navigating the fine cracks between them (2). Her pieces often address themes such as national identity, trauma, and displacement, bringing traditional rituals into public spaces and associating them with collective suffering. Based between Berlin and Amsterdam, Bartana critiques the rise of far-right movements and nationalism in Europe. Her Israeli and Jewish identity profoundly inform her art.

While this article will not delve into the complex debates surrounding Zionism—whether its roots lie in the “indigenous rights of the Jewish people in Israel for over 3,000 years” or “colonialist and imperialist occupation displacing Palestinians”—I aim to consider how Bartana uses the tools of science fiction to challenge the concept of “nation.”

Bartana’s 2024 Venice Biennale works must be understood as independent of any direct commentary on the recent tragedies and mutual destruction between Israel and Palestine, as their production predates the escalation of violence on October 7, 2023. This clarification is crucial to an accurate analysis of her art’s spiritual and political dimensions. To contextualize Bartana’s 2024 works, it is helpful to revisit her 2011 contribution to the Venice Biennale, where she represented the Polish Pavilion as the first non-Polish citizen to do so. Curated by Sebastian Cichocki and Galit Eilat, Bartana’s trilogy of films(3 (Mary Koszmary [2007], Mur i wieża [2009], and Lit de Parade [2011]) revolves around the activities of the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP). These films explore Israeli settlements, Zionist dreams, the Holocaust, and the Palestinian right of return, navigating a landscape scarred by competing nationalisms and militarisms.

“Profile” (2000), one of Yael Bartana’s early works, focuses on the three years of compulsory military service in Israel for both men and women and the shooting drills in the army. “Freedom Border” (2003) documents the launch and flight of a small airship during a military operation, with cameras mounted on its underside to monitor the country’s borders. In the photographic series “Herzl” (2015), Bartana takes on the guise of Theodor Herzl, the man who created the Zionist movement out of nothing and gave birth to the State of Israel. The genderless, fluid and at the same time Zionist portraits he creates by playing on archetypes and disguises in this work represent a metaphor for the ambiguous transitions between fiction and reality, utopian and dystopian, and make a sarcastic intervention against the idea of the nation-state. As we can see in her previous work, Bartana is interested in exploring the institutional forms of national identities, national ideologies, the idea of the nation-state and the collective/traditional/ritualized actions that underpin them.(4)

Approaches seen in her works often emerge from a present perceived as catastrophic, aiming to explore potential futures and alternative histories. This allows Bartana to engage with narratives of trauma and resistance, emphasizing the cyclical nature of history. In the German Pavilion, the “Thresholds” theme is addressed spatially and temporally. One of the clearest ways to understand the cyclical impact of “repetition” and “cycles” in space and time today is through intergenerational traumas.

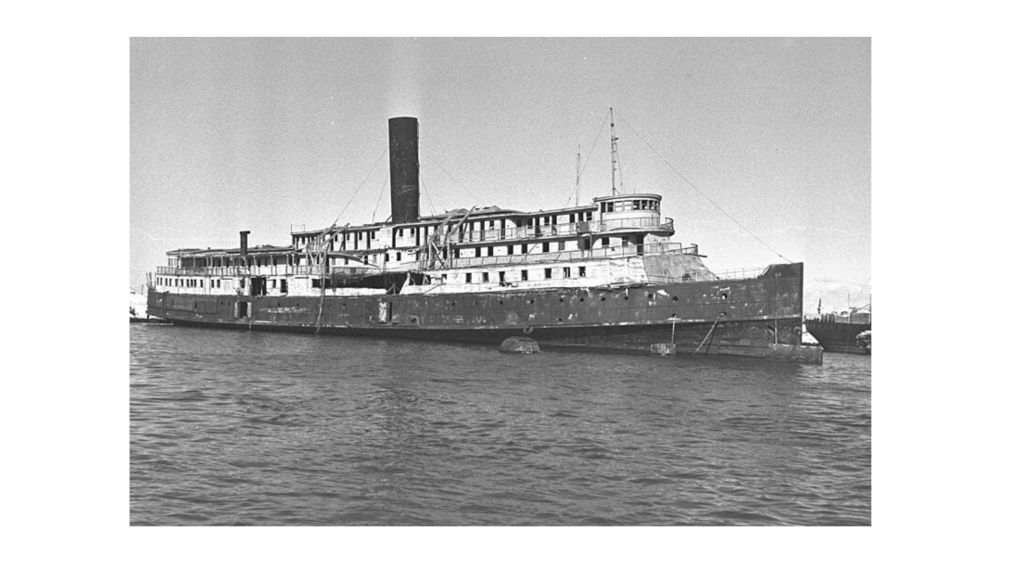

Photo: Exodus abandoned in Haifa.(6)

When reflecting on Light to the Nations, I was reminded of “Aliyah Bet,” the clandestine migration movement through which over 2 million Jews were secretly transported to Palestine between 1939 and 1948, escaping Nazi concentration camps. This operation, relying on volunteer efforts and large ships, became a lifeline for many. The SS Exodus ship, for example, attempted to carry a record-breaking 4,515 individuals to British Mandate Palestine, but was intercepted by British forces, subjected to gunfire, and forcibly returned to Nazi Germany.

Though Bartana does not explicitly address this history, as a viewer, I felt confronted by echoes of it. Viewing her work through the lens of causality and generational traumas, the installation offered a speculative, bird’s-eye perspective of inescapable historical loops—juxtaposing the Zionist narrative and Jewish indigeneity with science-fiction realities. In Light to the Nations, all nations sail into the depths of space aboard their unique spacecraft. Israel’s ship design becomes the focus of this imagined future.

Combining Zionism’s quest for belonging with the reality of science fiction and taking it to space, leaving the earth fallow and hoping for a collective and ecological recovery without human beings is a far-fetched dream even for any utopian and dystopian imagination, but Bartana instrumentalizes science fiction to offer us a wide range of perspectives to interpret current political, ecological and geographical tensions/destructions and proposes space as a way out and alternative futures that can be lived in space.

The connection of the human species to planet Earth and the soil, and gravity, is perhaps one of the main factors that at some point created the idea of “nation”. But how can nations, new generations and new societies exist in space if we are no longer connected to the earth? In this work, Bartana explores “spatial” and “temporal” forms of belonging, challenging traditional understandings of identity rooted in space. This approach highlights the shared experiences of “ non-belonging”, especially for those who are displaced or in a state of perpetual migration.

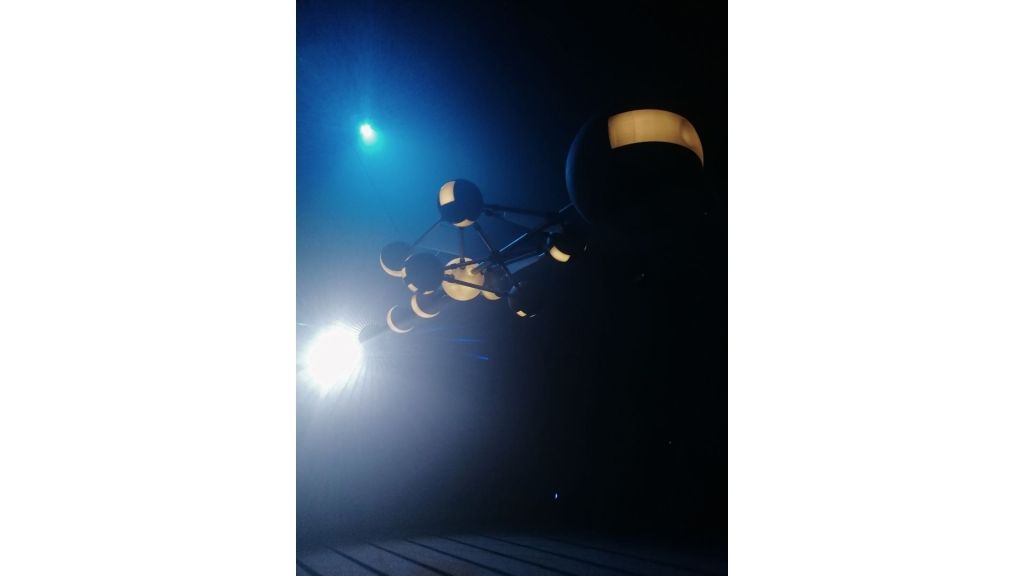

Photo: Light to the Nations – Generation Ship, 2024

3D model, 410 × 410 × 700 cm

“I, the Lord, have called you in righteousness;

I will take hold of your hand.

I will keep you and will make you

to be a covenant for the people

and a light for the Gentiles” Isaiah 42:6.

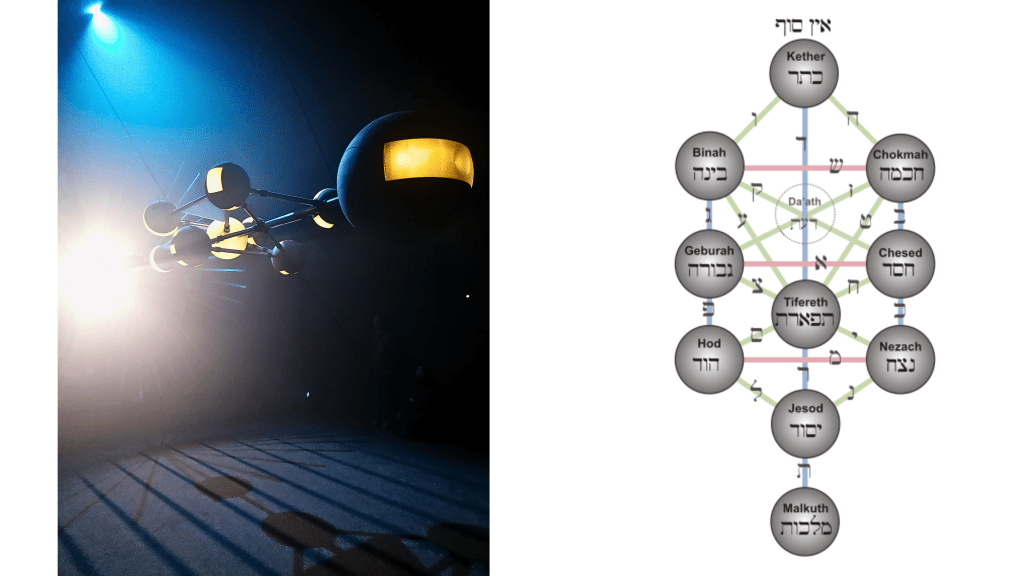

The 8th-century prophet Isaiah, in the Book of Isaiah—which contains the words of Amoz and is believed to have been written mostly during and after the Babylonian exile(6)—is seen by Bartana as issuing “a call to leadership”(7). Drawing on the diagram of the ten Sefirot from Kabbalah, she constructs a spaceship in her design. The Sefirot diagram, one of the key symbols in Jewish mysticism(8), is integrated into the spaceship’s design in this narrative, where “Light To The Nations” takes on a salvational mission by transporting people to new galaxies and planets.

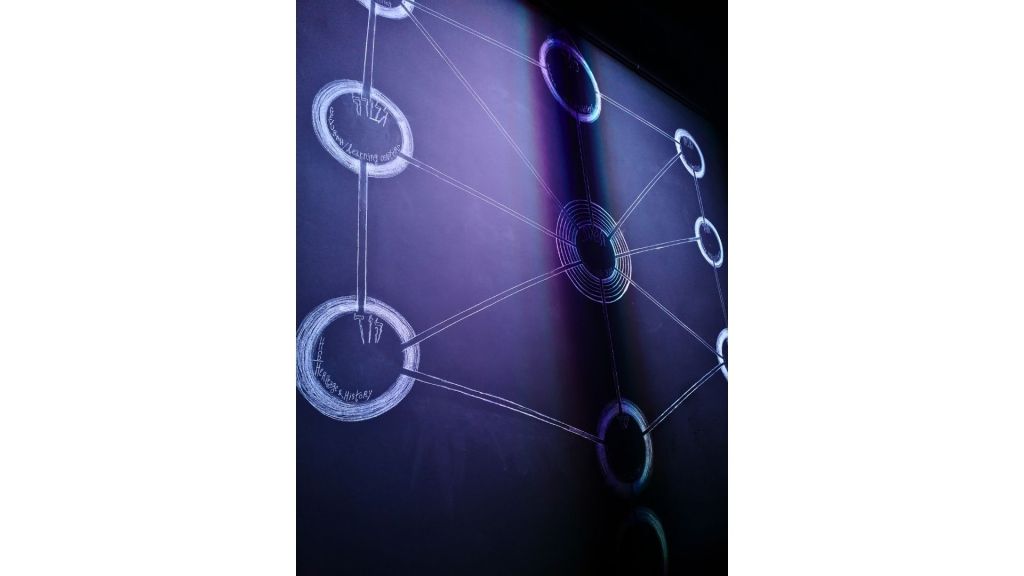

Photo: Sefirot symbol drawn on the wall with chalk.

This spaceship design is placed above human height, almost as if it embodies a great and unattainable ideal, a sanctified object. Surrounded by light play and sounds with different frequency ranges emanating from the spaceship, I sat on the ground for a long time, contemplating the connection between “Thresholds” and the Sefirot symbol while observing Yael Bartana’s Kabbalistic temple that envisions the future.

Each of the “Thresholds” appears centuries ago in the Kabbalistic system as part of the Sefirot Tree symbol, which describes the path of humanity’s arrival at Kether (infinite light). The Sefirot (or the opposite, known as “Klifot”) defines each threshold that humanity must pass in its return to the Creator’s light through evolutionary, cognitive, and mental dimensions. In the Kabbalistic Sefirot symbol, the uppermost Sefira (the singular of Sefirot) is “Kether” (Hebrew: כתר keter, “crown”). For Kabbalists, Kether represents the ultimate goal of spiritual seeking. It symbolizes pure divine existence and is so exalted that it is considered beyond human understanding, being called “the hidden of all hidden things” in the Zohar.(9) The first and lowest Sefirot, “Malkhut,” means “Earth”(10). Associated with the earth, Malkhut represents the human soul and the Oral Law. Looking at the entire Sefirot symbol, one can read a map of the journey from singularity to wholeness, from individuality to divinity; or, as seen in Bartana’s work, from earth to the heavens. Each of the ten Sefirot has transformed into various functional sections in Bartana’s ship, including a central hub, space research, engineering, medical center, education centers, agriculture, heritage, public spaces, living areas, and recycling centers.

Photo: Light to the Nations and the Sefirot symbol.

Bartana’s creation of this sci-fi temple, blending imaginary technologies with mystical teachings, envisions the spaceship as a Kabbalistic tool for spiritual salvation, aimed at approaching God’s throne. Moving toward a “utopian” ideal formed by religious elements, the future of humanity in space, having left its origins and planets behind, exposes both uncertainty and rootlessness, showing equally the “dystopian” side of these future ideals. The placement, proposing that humanity leave Earth as a solution to the ecological, geographical, and socio-political problems of an uninhabitable Earth on the brink of environmental and political collapse, invites us to reconsider the simultaneous existence of utopia and dystopia, where the boundaries of both are dissolved through these religious symbols.

To understand “Light to the Nations,” one must also understand the Kabbalistic concept of “Tikkun Olam.” A concept pointing to the promise of a better future, Tikkun Olam means “the repair of the world.”(11) In Kabbalah, the concept of “repair” suggests that sparks of divine light have scattered across the world, with some being lost. Tikkun Olam is the process of gathering these divine sparks and returning them to their source, carried out through ritual performances and spiritual practices. This foundational concept, felt behind the installation, is explicitly expressed through the 16-minute video and sound installation “Farewell.” “Farewell” depicts a ritual right before the spaceship’s departure to distant galaxies, a farewell ceremony.

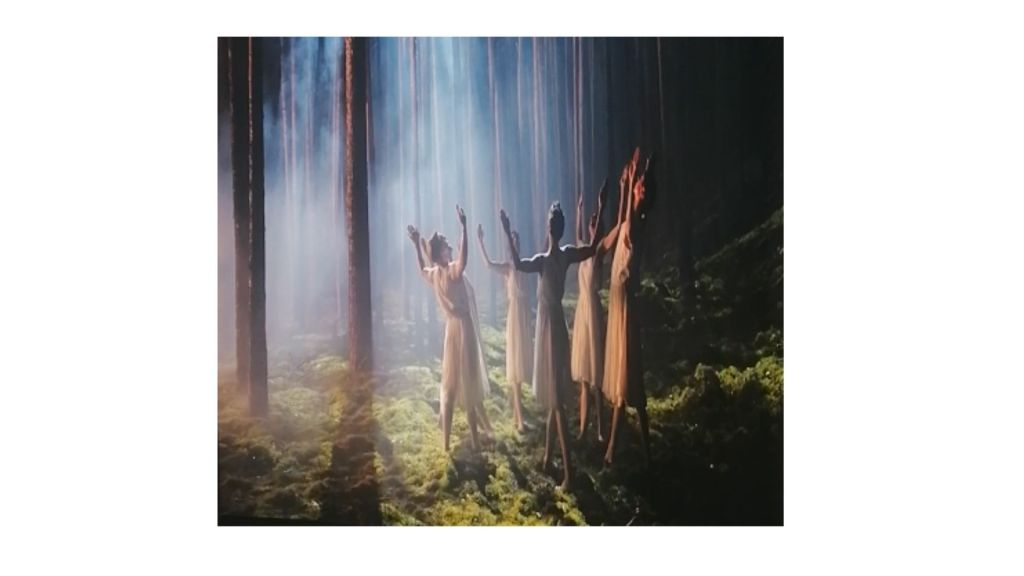

Here, dancers, through ritualistic choreography, send humanity off toward unknown places, evoking a powerful sense of unease. Bartana also draws from Labanotation, a system developed by Rudolf von Laban in the early 20th century, to create this choreography.(12) Laban’s expressionist dance style combines collective and ritualistic movement, reflecting Bartana’s connection with social themes. National identity, group rituals, and the social movements surrounding them—Bartana’s main research topics—are reinterpreted in “Farewell” using eclectic symbolic elements. The ritual marks a journey toward leaving Earth and salvation, emphasizing the existential crisis of humanity and the intertwined nature of the utopian and dystopian worlds born from this crisis.

In this piece, a “temporal belonging” is strongly felt, describing identity and connection that emerge from specific moments in time and ritualistic movement rather than fixed geographic locations. This feeling may be closely related to Bartana’s own experience of migration and the transient nature of belonging.

Photo: “Farewell”, Sound and Video installation, 16 minutes

Thresholds, as spatial and temporal transitions, are dimensionalities caught in between, that is, they describe an almost undefined and uncertain limbo. The curatorial strategy adopted for the presentation allows us to look at the present from different perspectives as a threshold where the past and the future intersect. In this context, “deterritorialized identities” that experience a break from a specific place or identity coincide with the nature of liminal spaces such as “Thresholds”. Thresholds provide belonging and citizenry of a spatial and temporal reality that remains unanswered between presence-absence / visible-hidden.

This vision in the curatorial method not only hides the content and meaning of the artworks, but also affects the historical and architectural fabric of the German Pavilion, in a way to de-territorialize the space itself. This curatorial strategy intervenes in the historical fabric of the space by placing Yael Bartana’s work in the same rooms as the works of Arno Breker, known as “Hitler’s favorite sculptor”, who had already occupied a place in the German Pavilion many years ago.This curatorial strategy intervenes in the historical fabric of the space by placing Yael Bartana’s work in the same rooms as the works of Arno Breker, known as “Hitler’s favorite sculptor”, who had already occupied a place in the German Pavilion many years ago.(13) In 1940, at the German pavilion, Breker’s works, which depicted “German superiority” with his perfectionist figurative sculptures, are now replaced by the spaceship design of Bartana, searching for her own belonging in the universe.

Yael Bartana’s works do not propose the standards of a nation or fragments of a transnational utopia; rather, by playing with the concept of the nation, creating artificial nations, or playing with the foundational values that created the idea of the nation, as well as proposing future scenarios where a stateless nation searches for its ultimate belonging, Bartana opens windows for us to view the current ideas of nations and communities from entirely different perspectives.

References:

1) https://deutscher-pavillon.org/en/deutscher-pavillon

2) https://www.yaelbartana.com/

3) These 3 films are about the Jewish Renaissance Movement (JRMiP). This movement is a Polish political group calling for the return of 3,300,000 Jews to their ancestral lands.

https://labiennale.art.pl/en/wystawy/yael-bartana-and-europe-will-be-stunned/

4) https://yaelbartana.com/work-items

5) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Exodus

6) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Isaiah

7) From Yael Bartana’s interview with Hanno Hauenstein, June 9, 2024.

https://spikeartmagazine.com/articles/yael-bartana-utopia-in-the-wrong-hands-can-be-very-dangerous

8) It is a matter of debate for many wether Kabbalah comes from the Jewish faith or whether Judaism comes from Kabbalah teachings.

9) https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kether

10) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malkuth

11) https://www.learningtogive.org/resources/tikkun-olam

12) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labanotation

13) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/calls-for-demolition-of-nazi-pavilion-in-venice2020066.html